Falls lead to injury, and in some cases, fractures. The cause of the fall needs to be carefully identified and appropriate interventions and investigations initiated to prevent further falls. Falls intervention does reduce falls and hospital admissions. The data on fracture reduction is not yet clear.

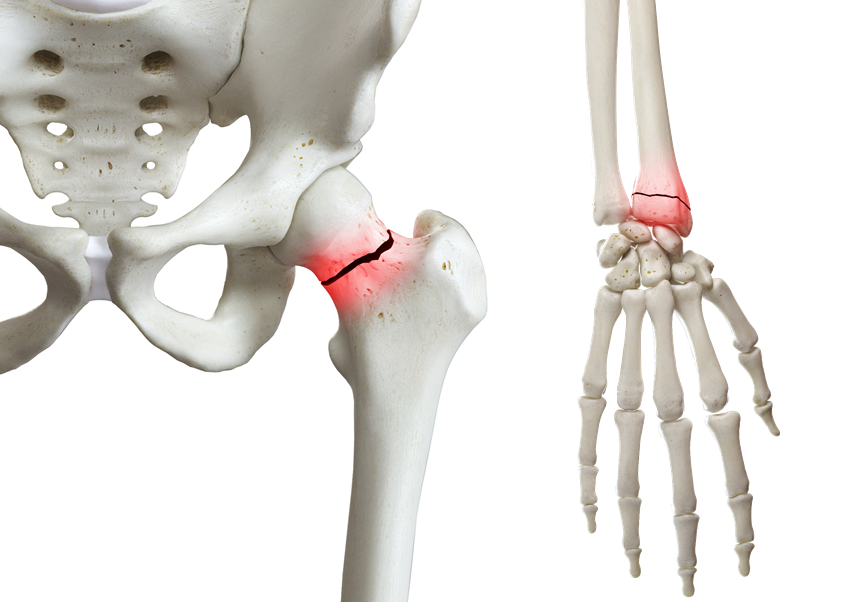

Though existing literature remains inconsistent regarding the relationship between ankle fractures and osteoporosis, most other fragility fractures are indicative of osteoporosis, and a prior fracture increases an individual’s risk of a subsequent fracture. The presence of a prior fracture and low bone density significantly increases the risk. Fractures of the hip, vertebra, pelvis, humerus, and wrist are all identified as osteoporotic fractures, and deserve investigation and treatment.

It is important to note that over half of individuals with hip fractures have had existing fractures. It is of interest that those subjects who have fractured are at twice the risk of subsequent fracture, and the phrase “fracture begets fracture” is worth remembering. A third of new fractures occur after an initial fracture in the first year. Both FRAX and GARVAN are good tools to identify fracture risk and the need for treatment. Low bone density can be associated with fractures, but most people who fracture will have bone density in the osteopaenic range.

Currently there are effective oral, sub-cutaneous and intravenous treatments to treat individuals who have had fractures. When discussing osteoporosis therapies, the side effects of osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fracture though rare, do need to be mentioned and explained to patients. All current therapies reduce recurrent fractures by 50% to 70% in most people.

There is compelling evidence now that calcium as monotherapy for osteoporosis is not effective. The available therapeutic agents for those with osteoporosis and fracture include Bisphosphonates, Teriparatide, Denosumab, Raloxifene, Romosozumab and Abaloparatide. It must be noted that not all the agents are available in all countries. It is important when choosing an agent that the side effect profile is examined and the therapy suits the individual patient.

The length of treatment is a topic of discussion. Most individuals should be treated for a period of at least 3 – 5 years. Those on bisphosphonates may have an off-treatment period of between 2 – 3 years, but need to be re-evaluated during, and at the end of this period. Those people who are at high risk and continued low bone density with pre-existing fractures, should be continued on treatment. Residual low bone density of the femoral neck appears to be an indication for continuing treatment. Those people who have completed a course of Teriparatide need to be considered for an anti-resorptive to maintain the benefits of Teriparatide therapy. Those on Denosumab when completing a course of treatment need to be considered for ongoing anti-resorptive treatment to avoid the chance of rebound vertebral fractures. Monitoring of patients is a clinical process that should be influenced by the occurrence of a new fracture, or by continuing bone mineral density (BMD) loss. Routine follow up of bone density measurement could be after 2 – 3 years of continuous treatment. Though side effects of some osteoporosis therapies, such as osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fractures, are rare, patients should be counselled about them.

There is compelling evidence that Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) are helpful in identifying patients with fractures who need to be treated and followed up. It is also clear that fractures cluster around the first fracture, and treatment initiation after the first fracture is important. This can help prevent the “fracture cascade” that otherwise will inevitably occur.

Dr Nigel Gilchrist, Canterbury District Health Board, Christchurch, New Zealand and APCO Executive Committee Member.